Fig. 01 Cattle on The Common – 1/60 at f/16, ISO 100

Introduction

Assignment 5 has a straight forward brief, the essence of which is to create a magazine story in the form of a picture essay and to design the cover of the magazine that will run the story. The final result should ideally incorporate both illustrative and narrative techniques.

As this assignment comes at the end of TAoP it is an opportunity to bring together elements of the whole course and it was always my intent to allocate a disproportionate amount of time to researching, planing and undertaking this assignment. TAoP naturally led me to researching a wide selection of established photographs, many of whom have very directly influenced my thinking even when their style or chosen field is not directly relevant to my own work but more than this influence they have collectively taught me a set of basic principles that I wanted to take forward into assignment 5 and beyond.

Working in a Series

The first principle, which is especially relevant to narrative, is that work is more effective when presented as part of a series. Nearly every photo book that I have studied and reviewed is greater, more powerful, than the sum of the individual photos within in. Sometimes this is because of the story line but often it is simply the effect of developing and building a conversation with the audience, exponentially drawing the viewer deeper into a subject as each image is revealed.

See – Planning Assignment 3 with Tony Ray-Jones and Martin Parr

Quality of Research and Understanding

The second principle relates to the ethics of documentary photography. Respected photo journalists such as Stuart Freeman (1), and Phillip Jones Griffiths (2) both point out the importance of the photographer immersing themselves in their subject so that their work respects and honestly represents it. Freeman states that “storytelling in photography must be as vigorous in thought and research as it is beautiful in construction and execution” and this aide has directed my whole approach to assignment 5.

This ideal is best summarised by a quote from Tod Papageorge (13).

“If your pictures aren’t good enough, you aren’t reading enough.”

See – Philip Jones Griffiths – An Engaged Observer

Contextualisation

The third principle flows from the second. Jones Griffiths points out that documentary images must be properly contextualised. His example is that a picture of a starving child is just that, it doesn’t mean anything. The photographer must provide the context, why is this child starving? what events led to this point? who is depriving him of food? Jones Griffiths believes that this can only be done by combining photographs with text, he argues that we live in a literal society so words are an essential element of photographic story telling.

See – Captions and Other Words in Photo Narrative and Phillip Jones Griffiths and the Use of Captions, Cutlines and Other text in Vietnam Inc.

Respecting the Subject Through the Quality of the Image

For the final principle I will refer back to the second part of the Freedman quotation. Understanding the subject is not enough, we must use whatever skills we possess to bring beauty to the construction and execution of the photographs. Exhibit one to support the case for this principle can be found in the work of Josef Koudelka (4) who has championed isolated and suppressed communities for much of his career and who makes these marginalised people important, human and valuable by the art and technical excellence that he brings to every one of his pictures.

See – Josef Koudelka – Wall and The Role of Olive Trees in Koudelka’s Wall

The Concept

Choice of Subject

It was always going to be important to select a subject that I already, at least in part understood, I felt that my classmate, Adam Newsome, had been so successful with his assignment 4 on IEDs (Adam’s Assignment) (5) because he had based it on a subject with which he was already intimate. This intimacy allowed him to explore and document the subject in real depth and to offer the audience an unique viewpoint.

I chose to look at my own childhood and the village in which I grew up.

Parallel Timelines

Having looked at a wide range of narratives and photo stories I wanted to develop a story line that had multiple strands. I had connected with Julian Germain’s For Every Minute You Are Angry You lose Sixty Seconds of Happiness (3) for many reasons but I especially responded to the idea of combining his “current” photographs with the subject’s own photographic memories, this gave the audience two timelines to follow and the opportunity for juxtaposing past and present. This worked well because Germain gave both sets of pictures equal prominence and therefore equal value, there was no suggestion that because the subject’s photos were amateur ‘snaps” that they should be treated with any less respect.

To enable me to introduce multiple timelines to my narrative I decided to base part of the story on the writings of George Sturt who lived in “my” village between 1891 and his death in 1927. Sturt was not a typical man of his times, a self confessed socialist who was also a business owner and employer and who saw his employees as people and friends. A number of his books are heralded as classics but his most moving works are a trilogy of books (6), (7), (8), based on conversations with his gardener whom he calls Bettesworth. Bettesworth, or Fred Grover, was an old man when Sturt first employed him and the stories of his life in a tiny Surrey hamlet tell the story of that village from the 1840s until his death in 1905. Sturt’s other book, Change in the Village (10) and his Journals continue to map the evolution of the area until Sturt’s own death.

The concept was to trace the spirit of Fred Grover and to document his path through this landscape and to overlay that with own childhood in the same place. I hoped to find places where Fred and I could meet and ideas upon which we might have agreed or even argued. I aslo wanted to draw on any similarities that I could find between my family history as it related the the village and Grover’s.

From the outset I wanted to use a small number of photographs from Grover’s time and from my family album. This would enable me to not only juxtapose past and present but to also provide visual variety.

Text and Captions

Whilst recognising and accepting that this assignment was about photography it was also clearly set as a magazine article and for that reason alone it needed text to complement the images. My study of the early photo stories had been informative but it was also obvious that this approach is now historic, Life and its competitors have long gone and the Sunday magazines, National Geographic and specialist magazines that are image heavy such as travel magazines have a high proportion of text to image. I am sure that there are examples of pure photo stories in magazines but I would more see this to be the province of the photo book or internet slide show.

More importantly I considered whose work had influenced me the most when researching narrative and quickly concluded it was Kodelka’s Wall, Jones Griffiths’ Vientnam Inc and Lam’s Abandoned Futures. Each of these books are heavily reliant on the written word to contextualise the photographs.

It also seemed relevant that as I would be researching the subject matter in some depth part of the story would only be told effectively by combining words with the photographs. I made the decision to format the story as if it was to be published in a magazine but to adopt a text / picture mix similar to Jones Griffiths.

Appropriation

The use of old photographs would already introduce an element of appropriation to the project but I was also keen to try and link the modern photographs with the past by using quotes from George Sturt’s books as captions. This approach also linked this assignment back to assignment 3 and my research into Anna Fox and Victor Burgin.

Other Influences

Different photographers and writers influenced different parts of the assignment.

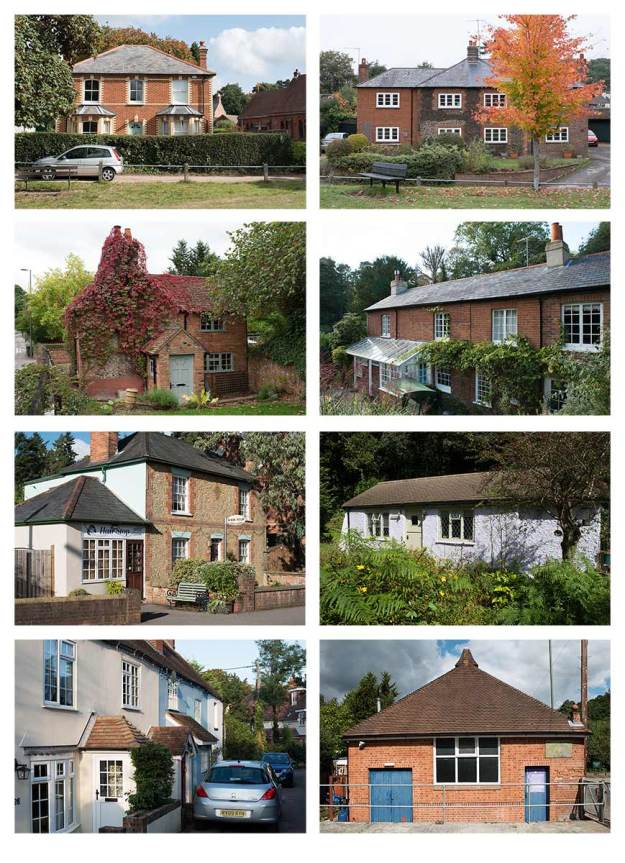

Joachim Brohm and the Bechers influenced the way I approached a double page spread typology of cottages and other buildings that I knew as a child and that Grover would have known.

I researched a number of different views on how a photo story should be created and took forward ideas from Harold Evans’ Pictures on Page (11) regarding layouts and the relationship between pots and text although there was, of course the need, to translate the ideas from broadsheet to a smaller format. His ideas on how to build a story are invaluable an, being a newspaper man, he likes words so further justified my essay writing. Equally useful was Derek Birdsall’s Notes on Book Design (12), his ideas on how to layout a page were inspiration even though I know that I fell way short of his high standards.

My general background research is summarised in my post Narrative andI endeavoured to carry forward that research into this assignment.

Overall my strongest influences were the photo journalists such as Jones Griffiths, who I have already mentioned, Stuart Freedman, Chris Steele-Perkins, and Eugene W. Smith (for Minamata rather than his work for Life Magazine). In each case these men talk about and follow the principles I have discussed above. Quite clearly they are usually documenting subjects of world importance and I had no such subject in leafy Surrey and their technical excellence is way beyond my limited skills but their real influence on me was to set a pace for the assignment that allowed me to become absorbed in my subject and think through the photographs I wanted and how I wanted to use them.

The Process

Developing the Concept

The concept was developed in parallel with the research described in Narrative but, even before I started with OCA, I was planning a project to look at the journeys of William Cobbett or the writings of George Sturt. Partly because they were both local men and partly because they wrote about the countryside I love and rural issues which are important to me and that always take a back seat in our urban dominated political landscape. However, I realised that the scale of the research required to deal with Cobbett was inappropriate for a single assignment and I also wanted to bring a personal element to the work and that would have been harder to achieve with Cobbett.

I felt that I already had a number of personal connections with George Sturt. My father had collected his books and as another passionate socialist shared many of Sturt’s views about the treatment of the rural poor. I had walked past his house everyday on my way to school and knew all of the places he wrote about but, more to the point, I knew these places not as a visiting student but as someone who had grown up in the lanes, fields and commons that he describes. His countryside was my countryside and it was this shared landscape that I mots wanted to explore.

Research

The first step was to re-read Sturt’s books and as I did this I formed a strong affinity with Fred Grover who had lived in a tiny cottage a few hundred yards from where I grew up, moving there around a hundred years before I was born. Sturt’s conversations with his old gardener revealed a complex life hidden behind the simple and stereotypical facade of the Surrey labourer and my copious notes centred around the important moments in Gover’s and, his wife, Lucy’s lives. His war service in the Crimea, the enclosure of the common, the birth and death of their children, Lucy’s decline as her epilepsy worsened, the shadow of the workhouse and destitution that was the end of the road for so many of the rural poor.

Each strand opened up new avenues of research including:

- Roger Fenton and his Crimean War photography, specifically searching on-line libraries for a photograph of the men of Grover’s regiment. I had looked at Fenton’s still life work during assignment 4 so it was interesting to look at a different aspect of his career.

- Farnham Museum, who were most helpful with searching their photographic archives for pictures of the 19th century village, Sturt’s house, Grover’s cottage and, after much searching, a single photo of Fred Grover himself talked by George Sturt.

- Simon Fairlie’s “A Short History of Enclosure in Britain” (15) was invaluable and provided much needed historic context and that helped explain Sturt’s thoughts on the matter.

- I met and talked to Wendy Maddox, who co-incedentially had been taught by my Father at The Bourne School in the late 1940’s, and who is an amateur but dedicated historical researcher who has carried out extensive work on the history of the village and specifically on the old graveyard. She was part of the team who identified Fred and Lucy Grover’s unmarked graves. The results of some of this research can be found on The Bourne Conservation Society website (16)

Photography

It is not really appropriate to describe my photography trips as shoots. Over a period of nearly three months I kept visiting the village, walking through different areas, talking to the people I met and taking photographs that seemed to capture the village I remembered. My aim was to find Grover’s spirit or part of my own history so other than starting my walks from obvious landmarks such as his cottage, Sturt’s house, the houses where I had lived, the school or the pub I did not plan shoots.

Over time I began to find themes and that invested my work with a little more purpose. I began to form an idea of wanting an element of typology in the final piece and a lot of my walks were in search of cottages that had been the homes of the original squatters who inhabited the village.

A number of my walks were on, what had been the common land, and is now either part of Frensham Common which is managed by the National Trust or The Bourne Woods which are owned by the RSPB and has become quite well know for its staring role in films such as Gladiator and Robin Hood.

My photographic technique changed significantly during this time as a heavy DSLR and camera bag became too restrictive and, given I was often photographing people’s home from the lane in front of their house, it also felt too invasive. Instead I started carrying a mirror-less Fuji XT-1 and this liberated my approach and led to, what seemed, simpler and more appropriate compositions.

Sources

Books

(3) Germain, Julian (2005) For Every Minute You Are Angry You lose Sixty Seconds of Happiness. Gottingen: Steidl MACK (Reviewed o line via a combination of Julian Germain’s web site – http://www.juliangermain.com/projects/foreveryminute.php and the MACK web site – http://www.mackbooks.co.uk/books/16-For-every-minute-you-are-angry-you-lose-sixty-seconds-of-happiness.html

(4) Koudelka, Josef. (2013) Wall: Israeli and Palestinian Landscapes 2008 – 2012. New York: Aperture

(6) Sturt, George. (1902) The Bettesworth Book: 1978 Edition, a facsimile of the second edition published in 1902. Firle: Caliban Books.

(7) Sturt, George. (1907) Memoirs of a Surrey Labourer: 1978 Edition, a facsimile of the second edition published in 1907. Firle: Caliban Books.

(8) Sturt,George (1913) Lucy Bettesworth. London: Duckworth & Co. Sturt, George (1907) Memoirs of a Surrey Labourer. 1978 facsimile of the 1st Edition. Firle, Sussex: Caliban Books

(9) Sturt, George (1912) Change in the Village. 1955 edition. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co.

(10) Sturt, George (1923) The Wheelwright’s Shop. First paperback edition 1963. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

(11) Evans, Harold. (1979) Pictures on a Page: Photo-journalism, Graphics and Picture Editing. London: Book Club Associates.

(12) Birdsall, Derek. (2004) Notes on Book Design. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Internet

(1) Freedman, Stuart. (2010) Ethics and Photojournalism – http://www.epuk.org/The-Curve/952/ethics-and-photojournalism

(2) Photo Histories (August 2014) – Philip Jones Griffiths – http://www.photohistories.com/interviews/23/philip-jones-griffiths

(5) Newsome, Adam. (2014) IEDs – https://adamnewsome.wordpress.com/2014/08/31/level-1-art-of-photography-assignment-4/

(13) Foto8. Mark Durden Interview with Tod Papageorge – http://www.foto8.com/live/tod-papageorge-interview/

(14) Smith, W. Eugene and Smith, Aileen M (1971) Minamata vs. Chisso Corporation – Magnum Photography site – http://www.magnumphotos.com/C.aspx?VP3=SearchResult&ALID=2TYRYDDWZXTR

(15) Fairlie, Simon (2009) A Short History of Enclosure in Britain. First Published in The Land Magazine – http://www.thelandmagazine.org.uk/articles/short-history-enclosure-britain

(16) The Bourne Conservation Society – http://www.bourneconservation.org.uk/index.htm