My tutor suggested that I looked at Nicky Bird’s Tracing Echoes (1) as a follow up to my TAOP assignment 5 submission, Change in the Village. This proved to be an interesting line of research that not only plays a part in closing down TAOP but has real relevance to various lines of research that I have subsequently been pursuing as part of Context and Narrative. With this in mind I am posting this essay on both learning logs.

Julia Margaret Cameron 1815 – 1879

I declare my prior ignorance regarding this obviously eminent Victorian photographer. Tracing Echoes includes, as way of an introduction, an essay by Pamela Gerrish Nunn which explains some of Cameron’s history and her place in the history of British photography. She is an artist worthy of study as her work, in many ways, is more closely related to the styles of the late 20th and early 21st century than to her own time. Gerry Badger (2) presents her as an unconventional photographer who “broke all the rules of 1860’s photography” and Pamela Gerrish Nunn explains that her disregard for conventions was not limited to her work behind the camera, she was a strong character who apparently often intimidated her sitters. Dr. Nicky Bird’s book mostly concentrates on her portraits of women, often in tableaux or as allegorical figures, so we have to look elsewhere (3) to find examples of her portrait style and how she often filled the frame with her subjects, sometimes working so close that the camera could not be focussed. This approach gives the viewer no escape, the frame is dominated by the subject and because we instinctively and subconsciously read body positions and faces we are joining Cameron in confronting her sitter and through this process are exposed to some element of their personality. Do they stare firmly back? Do they appear relaxed? Are they being made uncomfortable by the experience? Badger uses a photograph of Thomas Carlyle taken in 1867 to make the point that she was “totally at odds” with the usual formality of the Victorian portrait.

Diane Arbus (4) was a modern photographer who regularly used the same techniques to ensure that her audience did not miss the message when she photographed studies such as A Women in a Bird Mask or Women with a Fur Collar and many other of her street portraits, one might also look to some of Martin Parr’s work to see a similar approach. ( i )

I would like to return to Cameron in the future but, for now, my interest in is Nicky Bird.

Photography’s Relationship with History

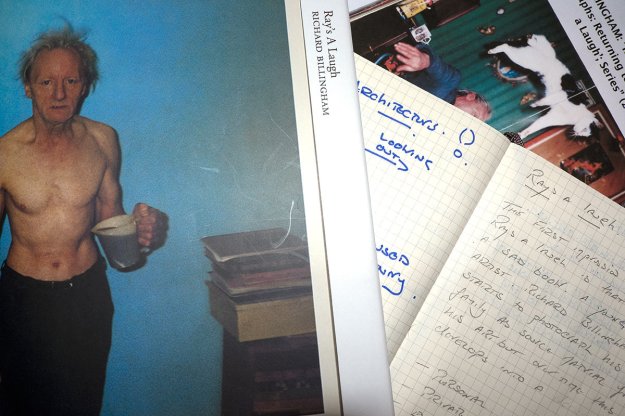

Tracing Echoes is a refreshingly affordable book and one that I am pleased to have added to my collection and, from my perspective, a book that is highly relevant to my work on Change in the Village and to my current research into Late Photography. Nicky Bird’s approach to photography speaks to my own interest in finding ways, by combining past and present photography, to understand how history has shaped us and our contemporary landscape. Photography records the present at the moment it becomes the past and since the 1860’s our understanding of history has become increasingly informed by the still or moving image. Today, television, on-line news and social media is consciously or subconsciously prioritised by the availability of images to such an extent that an un-photographed or un-filmed event is, at best, a footnote and, at worst ignored.

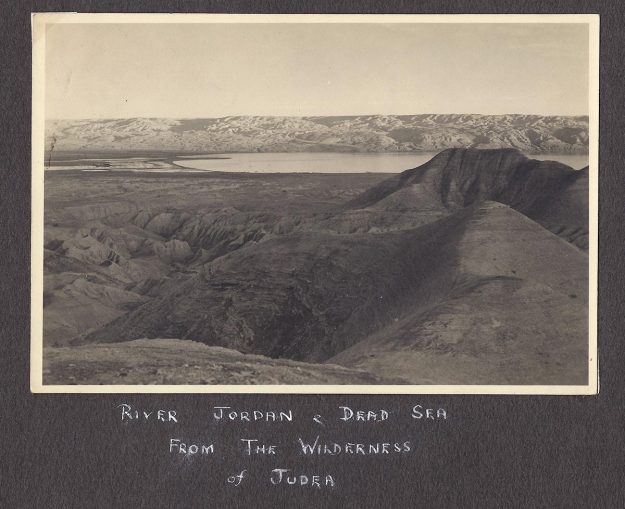

As a way of recording a place or an event photographs form part of the archaeological record but, beyond this, the photograph, in itself, is a physical or electronic artefact, a piece of archaeology. Most of us born in the 20th century have a record of our life in photographs forming a visual record of the places we have been, the physical and social changes we have experienced. This “family album” is a tiny current in the ocean of history but becomes more interesting when we attempt to link it with other contemporary or historic currents so it becomes part of a wider stream that tells a more comprehensive story of who we are and where we came from. In Change in Village I was trying to relate two lives that were separated by over a hundred years but played out on the same stage, a small Surrey village, and through this process I was exploring the way ideas and social interactions changed in a single place over time. I was also seeking traces of my life in that place and of the earlier life that had been lived there so the project was archaeological in nature with found images being the most commonly discovered artefacts.

Nicky Bird

Dr. Nicky Bird is a PhD Coordinator at the Glasgow School of Art (6) and a practicing artist whose work usually involves a combination of new and found photographs (7) to support explorations of social and hidden history. Tracing Echoes is one of her older published or exhibited projects dating back to 2001 when she was the artist in residence at Dimbola Lodge, the home of Julia Margaret Cameron.

In 2006/07 she created Question for Seller where she purchased unwanted family photos on ebay and exhibited them with the sellers comments and their original purchase price. At the end of the exhibition the photos were resold. This project raised a series of questions about the value placed on a family’s history and how a family album moves from being a cherished possession to a commodity that sells for a few pounds on eBay. In an interview with Sharon Boothroyd (8) the artist touches on how this process might be connected with class and the way in which working class history only exists at the margins. This is insightful and reminded me that the only reason I could trace photographs of Fred Grover, the real hero of Change in the Village, was because his middle-class employer had photographed him and that this family had placed sufficient value on their family album for it to survive and to be eventually donated to the local museum. I did not attend the exhibition but can only assume that the most asked question was “who are these people?”, a question that we ask ourselves when we pick up an photograph in a market. My mother left a biscuit tin of ancient family photographs and many are unnamed, undated and mysterious, I presume there is a connection with the family, that connection must have been important for my mother or her mother to have kept the photo but there the story ends.

Archaeology of the Ordinary was a series created in 2011 centred around a group of derelict cottages in East Lothian where archaeologists had found the signatures of, what proved to be, Irish migrant workers from the 1950s. Abandoned buildings hold a particular fascination as a place of ghosts and faint traces of history and perhaps because they have been abandoned as opposed to evolved and changed with the times adds a sense that the ghosts and traces are present but on the verge of disappearing forever. These migrants may have moved on and made their mark on the world in many other ways but it is also possible that some of these signatures are the only permanent record of their passing and it is this sense of seeing a moment in time in a photograph or a piece of graffiti and not knowing the back story or what followed that makes these marks, and Bird’s photos of them, so poignant. The idea and the approach of this and other examples of Bird’s work reminded me of an article in the British Archaeology Magazine about tree carvings or arboglyphs left by soldiers who trained on Salisbury plain showing, perhaps, that archaeology and photography sometimes follow the same as opposed to parallel paths. (10) ( ii )

Tracing Echoes

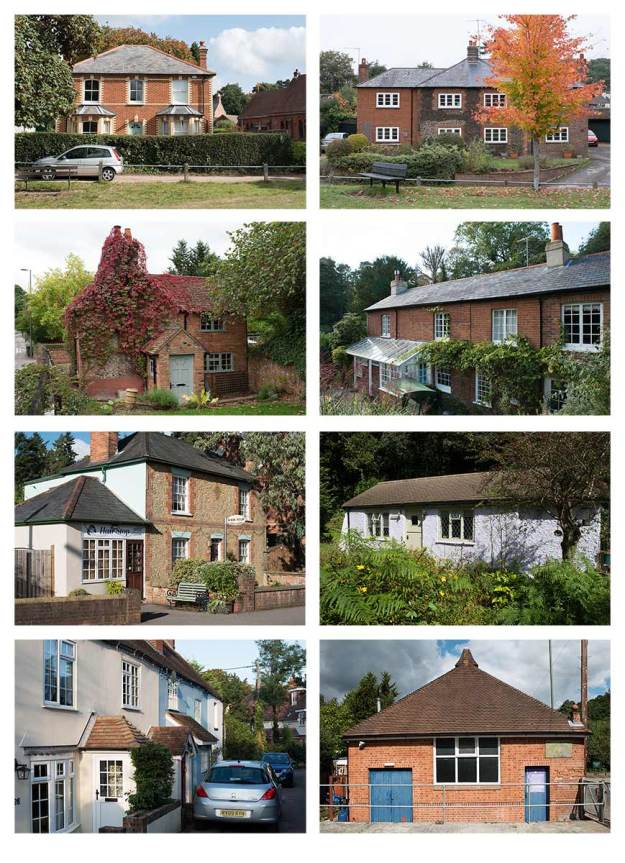

Tracing Echoes is divided into four main sections followed by a detailed conversation between the artist and two individuals from the National Museum of Photography. The first section sets out to map Dimbola Lodge, which as previously mentioned was the home of Julia Margaret Cameron in Freshwater Bay on the Isle of White. The presentation is of a single found photograph of the house in Cameron’s time and a series of new images taken by Bird. This acts as an introduction and gives a sense of place. I am interested that these images are quite flat, low contrast and without any artificial lighting for the interiors. This made me think of Jaochim Brohm’s Typology 1979 (11) which was part of my inspiration for Change in the Village, Typology 1979 is a study of the small structures Germans build on their allotments and was consciously photographed in flat autumn light. ( iii )

The second section, Timelines, is more interesting as each found photograph is accompanied by one of Bird’s images. The linkages between each pair are not always obvious and Bird makes no attempt to copy the composition and her images are all in colour. She explains that whilst some are of the same location there is a certain amount of guesswork involved and in one case we see Cameron’s daughter in 1867 and her bedroom as it is in 2000 which, as bedrooms have a special relationship with their occupants, this is a link that any parent or grandparent can relate to; the room is now stripped bare but showing it alongside a portrait of the daughter took me to the room in the 1860s asking me to imagine its Victorian decor. I found the subtle and unclear linkages drew me into the archaeological investigations asking me to linger over the photographs to find the clues and traces that Bird had seen or sensed.

There is then a section that records Bird’s genealogical research which I found needed to be read in conjunction with the conversation section at the end of the book that explains who these people are. However, that is a minor comment as any photo book worth owning must draw us back on multiple occasions and when the artist provides the level of context that we have here it will always be necessary to turn back and forth to understand the story. The genealogy searches tell us what happened to Cameron’s sitters which takes found photography to a different and interesting place partly, or perhaps mainly, because the sitters are mostly Cameron’s domestic servants or other working class people who visited the house. ( iv ) This research enabled Bird to make contact with some of the descendants of the sitters and thereby leading to the Echoes and Dialogues section.

It is worth noting that this research and, in some ways, the whole book is fuelled by Cameron’s tendency to note the names of her sitters on the back of the photographs. This is all the more surprising both because the pictures are often allegorical and because the sitters were working class, servants who would have been transparent to many upper middle class Victorians. Most other Victorian photographers and plenty of more modern ones did not take the trouble to find out or record who their subjects were so, as Bird points out, this act held some significant for Cameron despite the fact that some of these acquaintances were quite transitory, a fleeting visitor to the house for example. Cameron is an artist who is much studied and researched so the names of her sitters are well known and well published, the simple act of noting down their names has given these ordinary people an unusual status, a remarkable level of importance 150 years after they sat in front of Cameron’s camera so, for once, we are not asking “who were these people?”, a name gives them a more real existence, a history and, by tracing some of their decedents, a future.

The pairs of photographs presented in the Echoes and Dialogues section are not simply ancestor to the left and descendant to the right. Some are direct decedents, some are unrelated in the genealogical sense and Bird has linked the timeline through other means such as composition in Venessa at the Gate. Vanessa is Nicky Bird’s sister and quite unrelated to the original sitter, Mary Pinnock, the link is that they look similar, the pose is the same but it is not the same gate. Without going through each link suffice to say that they are varied and somewhat complex and I found myself drawn into the narrative to such an extent that I was turning back and forth between the photographs, the genealogical research and the closing conversation to understand the links.

Bird takes a place and shows it to us in the 1860s, she fills the place with the women who sat for a notable artist in that house and then draws us across 130 years to find that same place and another group of local women who are sometimes related to the original cast and sometimes not. This work is part historical research, part genealogy, part photographic and partly the study of a women who has an important place in the history of British photography and of women photographers and a exploration of Victorian values and the history of working class women. It appeals because it blends these disciplines in a practical and unforced manner, using research and photography as equal partners to tell an interesting story.

Notes on Text

( i ) When I made this statement I had in mind many of the close-up portraits that are included in Think of England (5). Plates 17, 19, 20, 24, 25, 58, 73, 82, 83, 104, 106, 107 and 108 are all examples where it might be argued that Parr has invaded the private space of his subject in a potentially confrontational manner.

( ii ) As soon as I saw Nicky Bird’s photos of these signatures I was reminded of an article in British Archaeology Magazine (10) in January 2013 about arborglyphs, the carving of soldiers names and often regimental badges into the trunks of the beech trees on Salisbury plain. All archaeology is about people but the stories become more moving the nearer they are to our own time, in the article the author, Chantel Summerfield, describes how she has traced some of these soldiers from their time training on Salisbury Plain to their service in WWI and sadly to their war graves in France or Belgium. One example combines a photograph of the arborglyph left by one solider with a found photo of his wedding day after the war, another shows a WWII arborglyph recording a soldier’s love for his wife Helen and found photos of the same lady in 1955. This latter story was quite poignant as although the American soldier in question had survived the war he had predeceased his wife but shortly before her death the author of the article had been able to send her a photograph of her husband’s carving of her name in a heart in a small wood on the other side of the world. Looking at this article again I realise that the dividing line between an archaeologist’s article and Nicky Bird’s work is very slight. The archaeologist offers us a higher ratio of words to pictures and her photographs are taken from the perspective of being a functional record but Nicky Bird’s Tracing Echoes also has a high percentage of text and the main difference is in the presentational style.

( iii ) One of the aspects I have struggled with when approaching landscape work during the course is that so many contemporary photographers appear rot actively seek out flat, low contrast lighting. I ask myself whether this approach is mandatory if one wishes to be taken seriously. If so, it is disappointing as I happen to like strong contrasts and saturated colours in landscape.

( iv ) Contemporary historians and archaeologists and the writers of fiction are increasingly interested in the stories of ordinary people following a long period where the world appeared to made up solely of the aristocracy and their servants without anyone in between. One of the great appeals of the work of Hilary Mantel, the two times Booker prize winner, is that her Henry VIII series is written from the perspective of the professional classes that served him.

Sources

Books

(1) Bird, Nicky (2001) Tracing Echoes. Leeds: Wild Pansy Press, University of Leeds in association wit the University of Northumbria at Newcastle

(2) Badger, Gerry (2007) The Genius of Photography: How Photography has Changed our Lives. London: Quadrille.

(4) Arbus, Diane (1972) Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph. Fortieth anniversary edition 2011-2012. New York: Aperture.

(5) Parr, Martin (2000) Think of England. Paperback Edition 2004. London: Phaidon Press.

(10) Summerfield, Chantel (2013) Landscape of Rememberance. British Archaeology Magazine January February 2013. York: The Council for British Archaeology

(11) Brohm, Joachim. (2014) Typology 1979. First Edition Published by MACK. Mack Books (a small selection of the plates can be seen at http://www.mackbooks.co.uk/books/1028-Typology-1979.html)

Internet

(3) J. Paul Getty Museum (accessed January 13th 2015), Jula Margaret Cameron Collection – http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/displayObjectList?maker=2026&pg=1

(6) Glasgow School of Art (accessed January 15th 2015) – http://www.gsa.ac.uk/research/supervisors-plus-students/primary-supervisors/b/bird-nicky/

(7) Bird, Nicky – Artist’s website (accessed January 11th 2014) – http://nickybird.com/profile/

(8) Boothroyd, Sharon (accessed January 14th 2014) Nicky Bird – https://photoparley.wordpress.com/category/nicky-bird/

(9) Bird, Nicky – Artist’s website (accessed January 11th 2014) – http://nickybird.com/projects/archaeology-of-the-ordinary-2011/