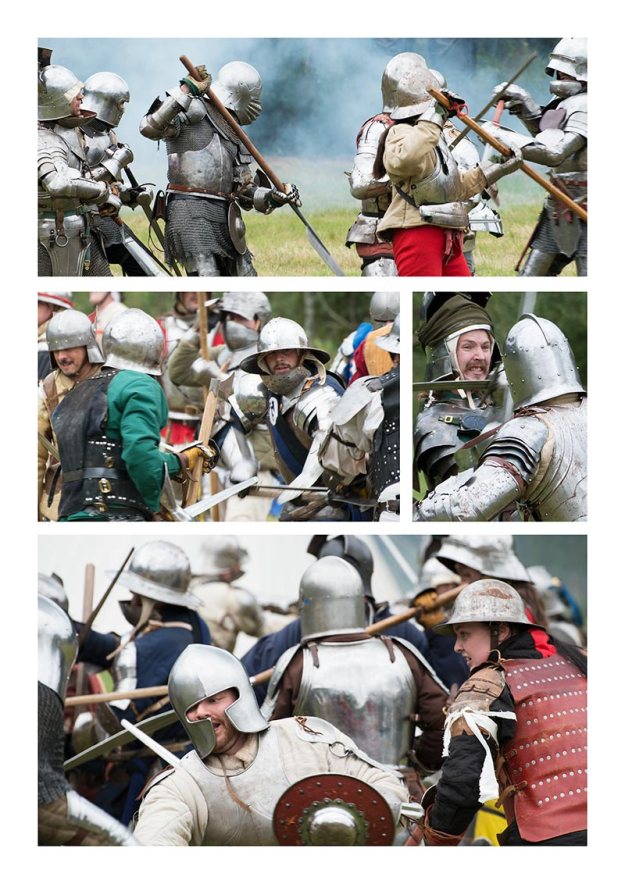

Fig. 01 The Full Loxwood Joust Five Page Spread

Exercise 40 calls for a picture essay of an event. I chose to cover the Loxwood Joust, a battle reenactment, medieval fair and joust held in the village of Loxwood, Sussex in August 2014. This event offered a variety of subjects but, for the photo essay, I concentrated on the first of two re-enactments and the joust as these offered the most colour and action. It would have been possible to add another page of store holders and perhaps a page of spectators but I decided to keep to an opening page and two double page spreads.

Fig 1 shows the layout of the spreads as if displayed in a magazine. I have not added any text other than the opening title which is arguably an unrealistic presentation but I was more concerned with practicing editing, selecting and displaying a story in a disciplined manner that writing about the event.

I am still researching the subject of narrative but, even at this early stage I am struck by the plethora of different terms used by various writers and the variety of interpretations of those terms. Harold Evans, in Pictures on a Page *(1), notes that the phrase photo story and photo essay are “used interchangeably in newspapers and magazines” but that an “essay [is] preferred by photographers who want to give themselves artistic airs”. He offers the following definitions:

The Picture Story: is essentially narrative, the record of a single event or aspect of it, or a simple chronology. It may imply a comment but it is descriptive rather than declarative.

The Picture Essay: is not confined by time or event. The essay will argue and analyse rather than narrate: it will make points.

Michael Freeman, in The Photographer’s Story *(2), says that the photo essay was a term coined by Life Magazine in 1937 to promote the “photographic story as an advanced form that went beyond a collection of pictures”. His definitions, which seem to conflict, at least in part, with Evans, are:

The Picture Story: photographs can be harvested from many sources.

The Picture Essay: implies a single vision and the work of one photographer shooting in a consistent style.

Putting this confusion to one side for later discussion it is perhaps more important to focus on the word narrative which seems to be more universally understood to mean the telling of a story. David Campbell, in his talk on narrative *(3), is very clear that “narrative is an account of connected events” so whether we wish to give ourselves “airs” and call this an essay or settle for it being a story is neither here nor there.

Loxwood Joust is the story of a day in a rather pretty corner of the Sussex countryside, it is not the whole day because all narrative is about inclusion and exclusion; Ian Fleming might have been less successful if each of Bond’s love scenes was preambled by a detailed description of the bedroom wallpaper and the exact dimensions of the bed. I have selected the best bits of the story that could be fitted into five pages. The twenty four photos are not necessarily the best I took on the day but they appear to tell the story; however, as Evans points out the photographer is potentially the least qualified person to make the selection. He refers to Michael Rand who was once the Art Director at The Sunday Times Magazine who believed that photographer’s do not know their best pictures, “they get too involved with them. They try and tell you what the picture is saying…. if I can’t see it I don’t want it explained.”

So, Loxwood Joust is my selection of photographs laid out in picture story style but without text or context. They attempt to tell a story by:

- Introducing the cast and thereby giving the story a face;

- showing two mock conflicts for the sake of dramatic effect.

- suggesting a chronological sequence that closes with the participants leaving the field.

Technique and Thoughts for the Future

Most of the portraits were taken with daylight flash, a technique I have been practicing ever since reviewing Martin Parr’s Last Resort. This technique is tricky, the flash gun needs to be constantly adjusted to increase and decrease its power as the light and the distance form the subject changes. However. it gives me more control when working against the clock, at an event like the Joust most of the characters are happy to be photographed but there is still limited opportunity for stage management to move people into the right light so being able to get fairly predictable and quick results regardless of the position of the sun is a real bonus. I also like the slightly 3D effect that the flash gun sometimes imparts.

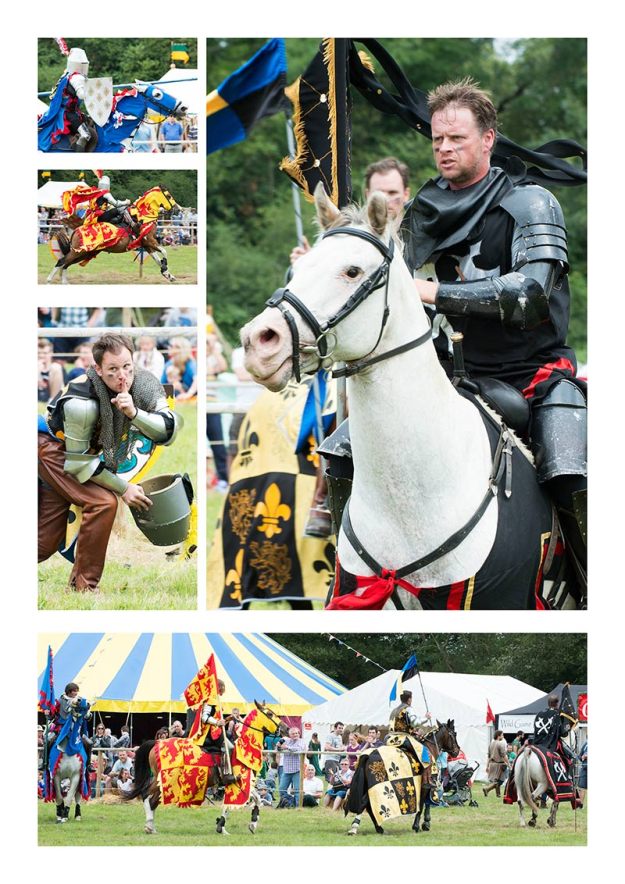

The long range shots were taken with a 70 to 300mm lens. I sacrificed depth of field for speed but the left the ISO on auto so the camera was selecting exposures based on 100 ISO whenever it could. I now realise that I would have been better to set the ISO at 400 and gain a extra couple of stops of aperture and thereby have more often captured the nearest and furthest horse in focus. I was side on which was not ideal and a 45 degree angle would have probably reduced the need for depth of field and captured the moments of impact more effectively.

I researched the event as much as was possible but a site visit would have been useful and, in hindsight, I should have tried to get some sort of accreditation that would have allowed me better access to the arenas. For the battle I was able to get a prime spot but I was late arriving at the Joust arena and most of the ideal spots were taken.

This was only the second re-enactment I have been to and it is worth remembering that the participants are only too happy to be photographed. If you are willing to dress in medieval armour and fight a mock battle you are happy to have your picture taken. I enjoyed the close-up studies more than the battles and enjoyed the interaction with some colourful characters.

The Spreads

Fig. 02 The Opener

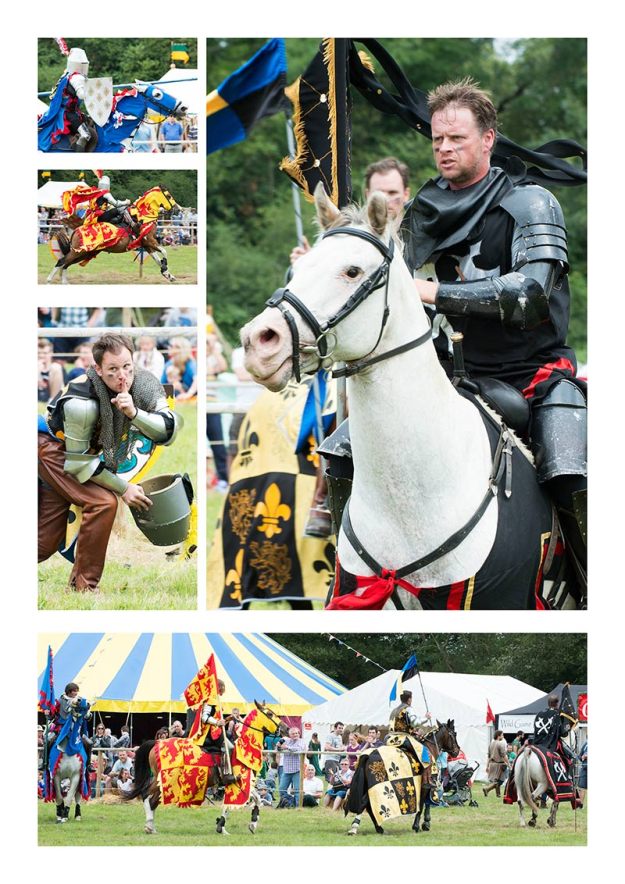

Fig. 03 Introducing the Cast and the Battle of Loxwood

Fig. 04 The Joust Through to Close

The Individual Pages

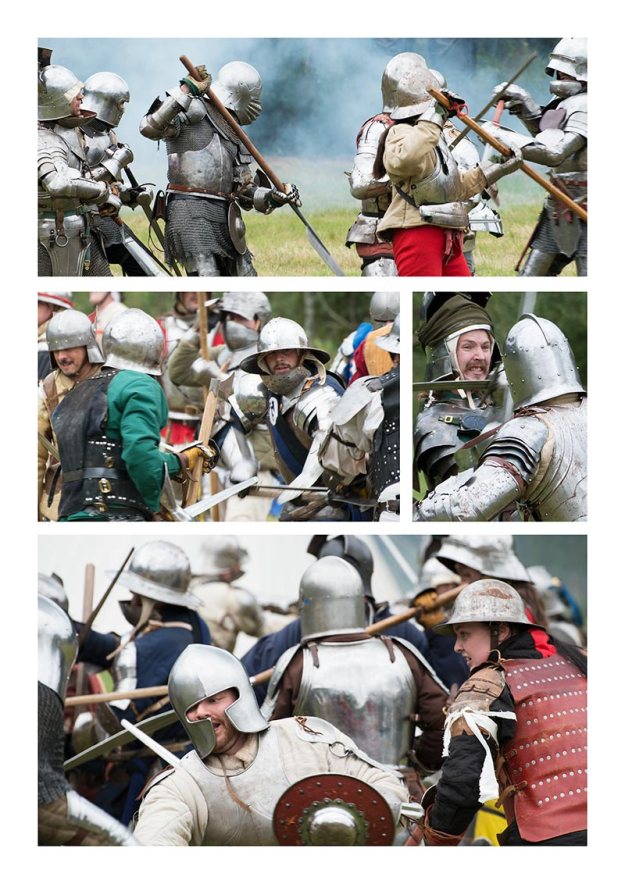

Fig. 05 The Opener

Fig. 06 Some of the Cast

Fig. 07 The Battle of Loxwood

Fig. 08 The Joust

Fig. 09 Close

Sources

(1) Evans, Harold. (1979) Pictures on a Page: Photo-journalism, Graphics and Picture Editing. London: Book Club Associates.

(2) Freeman, (2012) The Photographer’s Story: The Art of Visual Narrative (Kindle Edition). Lewes: Ilex Press.

Internet

(3) Campbell, David. (2010) Photography and narrative: What is involved in telling a story? – http://www.david-campbell.org/2010/11/18/photography-and-narrative/

Campbell, David. Official Website – http://www.david-campbell.org

(3) Soundcloud, recorded by Matt Johnston. David Campbell – Narrative, Power and Responsibility – https://soundcloud.com/mattjohnston/david-campbell